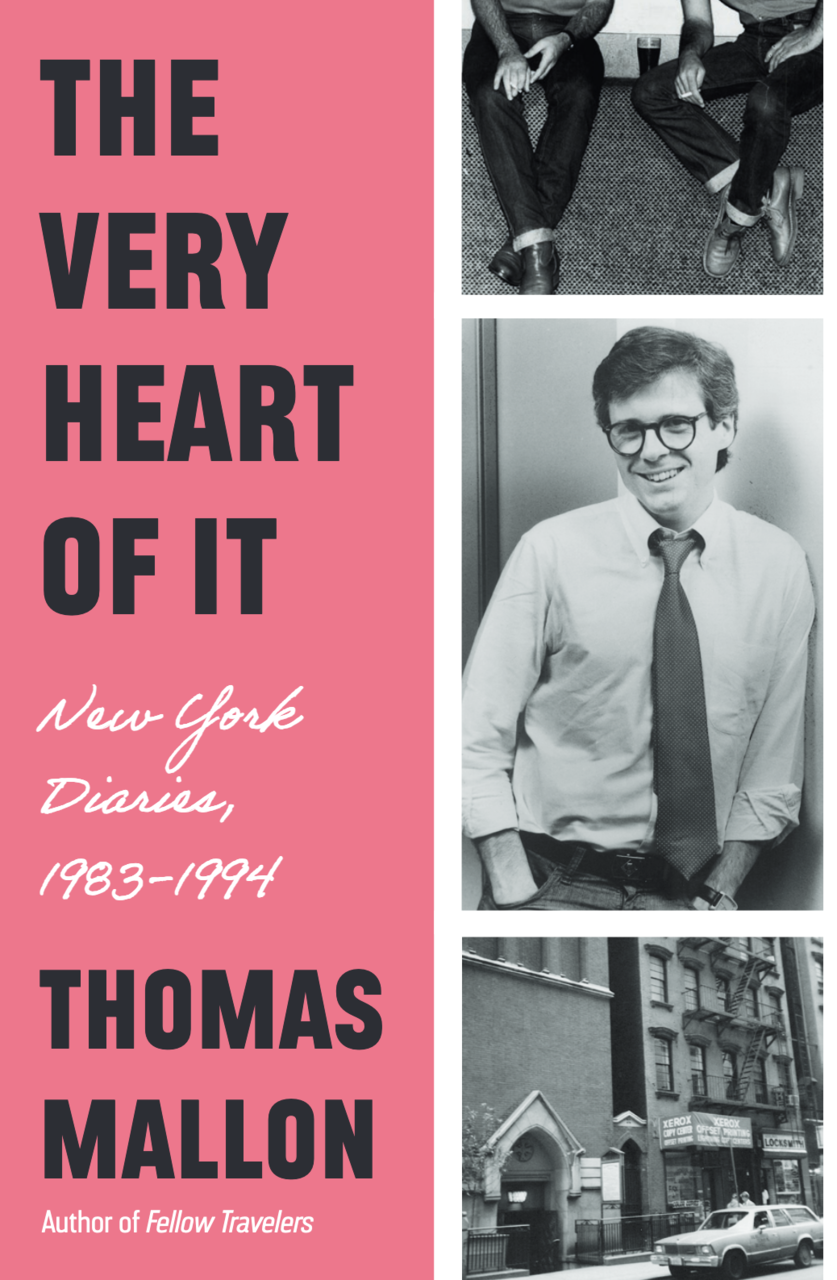

Thomas Mallon’s New York Diaries Are About You

Cover courtesy of ThomasMallon.com

Big emotional swings power Thomas Mallon’s newest, The Very Heart of It: New York Diaries, 1983-1994, out from Knopf in 2025. Not only do readers get to swing across the wide arc of human emotion, the G-forces of traveling from love to fear to lust to wit-fueled shit talking in their hair, but there is a second kind of swing in motion as well: for the fences.

Mr. Mallon chatted with Moss Heart Books via email about the book, which recounts his era of Really Going For It, a time in his life that paralleled similar action in the world, and specifically in America, characterized by big swings all around. He details his forays into bigger and more prestigious teaching and writing positions, as well as his utter sadness at witnessing young men dying from AIDS, while writing, sometimes on the same day, about a kind of twinkling joy of being out there in the world.

It’s thrilling as hell, even the despair.

All of this is backdropped by the now familiar financial shifts of the 1980s and early 1990s, the oft-covered Political strife and successes, as well as the sociopolitical changes and a front-row seat to the horrors of the AIDS epidemic. But this is not a sad book! There are sad parts of it, but there are miraculously joyful parts of it as well.

Mallon had feet on the pavement in New York City as his life began to swing into a new era right alongside the best-known city in the world. This book is a record of his experiences, of his loves and losses, and yes also of his petty literary opinions (which I adored reading), and of a love story that brought a third swinging into the mix, that being the slightly scary but oh-so thrilling swoop of a new-found love landing in your heart’s four quadrants.

It’s all wrapped up in one word, a proper noun, which you’ll see below as well: Bill.

I first encountered Mr. Mallon’s work due to my obsession with the Watergate scandal. He wrote a novel, simply titled Watergate, that drew me into his work and led me here. I do wish I could send a small audio message back into the 1980s, to let it subtly ride on a gust of wind so as to not upset the spacetime continuum, where it would find a young Mr. Mallon’s ears. I would whisper, “You are a novelist,” because his diaries detail his mental and emotional battles over writing fiction versus non-fiction, specifically critique.

I doubt my time-piercing message would change much. Those words mean the world for almost exactly 10 seconds, then the struggle with the page begins again. Plus, I’d hate to potentially rob myself of his diaries detailing those days and nights he despaired, only to then march forward and work for places like The New Yorker, The New York Times Book Review, and GQ.

A failure is just the first act of a success.

Plus, I think the title of this fantastic collection requires that struggle. What is “the very heart of it” and in fact, what is the “it” in question? Either Mr. Mallon never comments on this in his diaries or I forgot what he said because I was too obsessed with other things (see: Sontag).

But, based on having read this and of having fallen in love with all its imagery, with Mallon’s writing more and more, and yes with he and that Proper Noun, I think “it” is…Us. Humans.

And in this case, our “very heart” isn’t our body’s literal organ, but the act and necessity of swinging between emotions. And what a privilege it is to have all these different feelings inside of us, and to have a book that takes us into the intoxicating and slightly scary bits, but also into goofiness and stodginess and everything in between.

-•-

Moss Heart Books: One of my favorite juxtapositions of tone in your entries happens in two December 1984 entries. The 15th sees you talking to Carl, joking about finding a "sidewalk Santa" to sleep with, followed by December 19th, which reads in its entirety: "Getting off the train at Christmastime with my students: one of the few times I'm in love with the idea of being a teacher.”

The 15th's entry is playful, funny, a little naughty and the next reads as heartfelt but also a bit sad. You're not teaching in the entry, you’re in love with the “idea” of being a teacher.

Were there insights you gained into your head and heart while coming across entries that showcase varied emotions?

Thomas Mallon: Interesting that you should mention teaching. Publishing the diaries (as opposed to just reading or even editing them) brought me a really new perspective on that part of my life. I’m quite unkind to Vassar in the diaries—I feel overburdened, disgusted with campus politics and so forth. But I’m cranky mostly because I want to be writing, to give my entire time to it. As a result, even though I worked hard at teaching, I tended to resent and undervalue it. It was my “day job,” which I wanted to quit.

Well, a few months ago, after the diaries were published, I started hearing from old students of mine: really generous communications in which they mentioned how much they remembered my classes, how much they’d learned, and so forth. As a result, teaching has begun to take a different shape in my memory: as much as I was struggling to get out from under it back then, I was accomplishing more than I realized.

MHB: Your journals give readers a unique view into a historically impactful time in America, specifically the arrival and rise of "Reaganism" and the AIDS epidemic. At one point you talk about being a gay conservative and how people would be surprised how many gay conservatives there are.

How did entries like this feel to you as the book came together, knowing American politics (big P and small p) has steadily reduced nearly everyone to binary identities?

TM: I have never liked hook-line-and-sinker partisanship. As the years went on I was appalled by how indifferent to AIDS Reagan appeared. But why should that keep me from admiring the effectiveness of his anti-communism vis-a-vis the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe? (I would many years later try to dramatize this divided mindset in my novel Finale, through the character of Anders Little.)

Going back to the diaries made me feel that the ‘80s were a far more vital political time than the one we’re in now. People weren’t “cancelled.” They had victories and defeats and they lived to fight another day. The personalities (Reagan, Thatcher, Cuomo, Koch), whether you liked them or not, were big and authentic. And they generally believed what they were saying.

MHB: I became quite invested in yours and Bill's relationship throughout and am curious about the editing process for the overall book. Yours and Bill’s lives become a “storyline,” of sort. Was this strange to witness, or was it slightly life affirming? Are we all simply in various acts of various stories?

TM: The first time Bill appeared in the diaries, when we met in early 1989, I misspelled his surname. Strange to think that 36 years later I’d be dedicating this book to him and thanking him for the thirteen thousand or so days between then and now. To answer your question, I’d say the whole experience has been both: strange and life-affirming.

I presented Bill with the entire manuscript when I’d finished editing it. I said he could cut any—or all—references to himself. I could end the book in 1988 if need be. I was nervous as he read it over the course of a week or so. I asked him to hold off on telling me his reactions as he went along, and to let me know only when he finished. When he was done, he came into my study one night to say I should publish the whole thing. The last two-hundred-plus pages were the story of our life together, as we lived it day by day, and it was fine to put it out into the world. His answer became one of the many things for which I’m grateful to him.

MHB: Readers (and viewers, etc.) can feel ownership over the entertainment we enjoy, as well as the artists responsible. Do you worry much about readers viewing you as a fictional creation for them to enjoy? Or not enjoy?

Illustration courtesy of ThomasMallon.com

TM: No. Some readers will like me, and some readers won’t. And I’m fine with that. There’s a narrative flow to the book, but I don’t worry that I’ll seem more like a fictional character than, say, the protagonist of any conventional memoir or autobiography does. There are a lot of different moods in the more than five hundred pages—as there are with anyone’s life experience. As grim as the AIDS subject matter is, readers will find a lot of funny parts, and I’m happy for them to be entertained by them.

MHB: Were there thoughts or discussions on how to end the book? I admit I rushed to the internet to find certain answers after the book was over.

TM: I suppose I was looking for a narrative arc, and I chose to end things in 1994, when I was finally having success as a fiction writer and not just a critic. My struggle to gain an identity as a novelist is one of the “plot lines,” I guess, and I thought that going out on a high note might be a good idea. The ending also emphasizes my luck—how I was one of those that fate allowed to go on living.

MHB: In 2025, is there any moment in the book you feel showcases such a massive change within you that the young man who wrote the entry would simply not believe it to be true?

TM: Maybe the moment that comes closest to that occurs on March 9, 1988, when I make a decision to give up my tenured job and bet everything on becoming a writer. What made me happy rereading that was seeing how I took this decision not when I was feeling confident, but just after I’d had a big setback. I’ve been a conventional person is most respects, very security- minded, but this was a rare moment when I showed a bit of daring. And I’ve never regretted it.

-•-

Thank you so much to Thomas Mallon for chatting via email. If you’d like to buy a copy of The Very Heart of it, please reach out via our contact page here or through our Instagram.

-Austin Wilson

Moss Heart Books Owner/Operator